JOSEPH OUR PARISH PATRON SAINT AND THE UNIVERSAL CHURCH.

St. Joseph (flourished 1st century CE, Nazareth, Galilee, region of Palestine; principal feast day March 19, Feast of St. Joseph the Worker May 1) was, in the New Testament, Jesus’ earthly father and the Virgin Mary’s husband. St. Joseph is the patron of the universal church in Roman Catholicism, and his life is recorded in the Gospels, particularly Matthew and Luke.

Champaigne, Philippe de: The Dream of SaintJoseph The Dream of Saint Joseph, oil on canvas by Philippe de Champaigne, 1642–43; in the National Gallery, London. 209.5 × 155.8 cm.(more)

Joseph was a descendant of the house of King David. After marrying Mary, he found her already pregnant and, “being a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace” (Matthew 1:19), decided to divorce her quietly, but an angel told him that the child was the Son of God and was conceived by the Holy Spirit. Obeying the angel, Joseph took Mary as his wife. After Jesus’ birth at Bethlehem in Judaea, where the Holy Family received the Magi, an angel warned Joseph and Mary about the impending violence against the child by King Herod the Great of Judaea, whereupon they fled to Egypt. There the angel again appeared to Joseph, informing him of Herod’s death and instructing him to return to the Holy Land.

Avoiding Bethlehem out of fear of Herod’s successor, Joseph, Mary, and Jesus settled in Nazareth (Matthew 2:22–23) in Galilee, where Joseph taught his craft of carpentry to Jesus. Joseph is last mentioned in the Gospels when he and Mary frantically searched for the lost young Jesus in Jerusalem, where they found him in the Temple (Luke 2:41–49). Like Mary, Joseph failed to comprehend Jesus’ ironic question, “ ‘Why were you searching for me? Did you not know that I must be in my Father’s house?’ ” The circumstances of Joseph’s death are unknown, except that he probably died before Jesus’ public ministry began and was certainly dead before the Crucifixion (John 19:26–27).

Some of the subsequent apocryphal narratives concerning Joseph are extravagantly fictitious. The 2nd-century Protevangelium of James and the 4th-century History of Joseph the Carpenter present him as a widower with children at the time of his betrothal to Mary, contributing to the confusion over the question of Jesus’ brothers and sisters. The allegation that he lived to be 111 years old is spurious. Reliable information about Joseph is found only in the Gospels, for the later pious stories distort his image and helped delay his commemoration.

Although the veneration of Joseph seems to have begun in Egypt, the earliest Western devotion to him dates from the early 14th century, when the Servites, an order of mendicant friars, observed his feast on March 19, the traditional day of his death. Among the subsequent promoters of the devotion were Pope Sixtus IV, who introduced it at Rome about 1479, and the celebrated 16th-century mystic St. Teresa of Ávila. Already patron of Mexico, Canada, and Belgium, Joseph was declared patron of the universal church by Pope Pius IX in 1870. In 1955 Pope Pius XII established the Feast of St. Joseph the Worker on May 1 as a counter-celebration to the communists’ May Day.

THOMAS MORE THE PATRON SAINT OF LAY FAITHFULS CELEBRATED JUNE 22.

Thomas More was born in 1478, son of the lawyer and judge John More and his wife Agnes. He received a classical education from the age of six, and at age 13 became the protege of Archbishop John Morton, who also served an important civic role as the Lord Chancellor. Although Thomas never joined the clergy, he would eventually come to assume the position of Lord Chancellor himself.

More received a well-rounded college education at Oxford, becoming a “renaissance man” who knew several ancient and modern languages and was well-versed in mathematics, music and literature. His father, however, determined that Thomas should become a lawyer, so he withdrew his son from Oxford after two years to focus him on that career.

Despite his legal and political orientation, Thomas was confused in regard to his vocation as a young man. He seriously considered joining either the Carthusian monastic order or the Franciscans, and followed a number of ascetic and spiritual practices throughout his life – such as fasting, corporal mortification, and a regular rule of prayer – as means of growing in holiness.

In 1504, however, More was elected to Parliament. He gave up his monastic ambitions, though not his disciplined spiritual life, and married Jane Colt of Essex. They were happily married for several years and had four children together, though Jane tragically died in childbirth in 1511. Shortly after her death, More married a widow named Alice Middleton, who proved to be a devoted wife and mother.

Two years earlier, in 1509, King Henry VIII had acceded to the throne. For years, the king showed fondness for Thomas, working to further his career as a public servant. He became a part of the king’s inner circle, eventually overseeing the English court system as Lord Chancellor. More even authored a book published in Henry’s name, defending Catholic doctrine against Martin Luther.

More’s eventual martyrdom would come as a consequence o f Henry VIII’s own tragic downfall. The king wanted an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, a marriage that Pope Clement VII declared to be valid and indissoluble. By 1532, More had resigned as Lord Chancellor, refusing to support the king’s efforts to defy the Pope and control the Church.

In 1534, Henry VIII declared that every subject of the British crown would have to swear an oath affirming the validity of his new marriage to Anne Boleyn. Refusal of these demands would be regarded as treason against the state.

In April of that year, a royal commission summoned Thomas to force him to take the oath affirming the King’s new marriage as valid. While accepting certain portions of the act which pertained to Henry’s royal line of succession, he could not accept the king’s defiance of papal authority on the marriage question. More was taken from his wife and children, and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

For 15 months, More’s wife and several friends tried to convince him to take the oath and save his life, but he refused. In 1535, while More was imprisoned, an act of Parliament came into effect declaring Henry VIII to be “the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England,” once again under penalty of treason. Members of the clergy who would not take the oath began to be executed.

In June of 1535, More was finally indicted and formally tried for the crime of treason in Westminster Hall. He was charged with opposing the king’s “Act of Supremacy” in private conversations which he insisted had never occurred. But after his defense failed, and he was sentenced to death, he finally spoke out in open opposition to what he had previously opposed through silence and refusal.

More explained that Henry’s Act of Supremacy, was contrary “to the laws of God and his holy Church.” He explained that “no temporal prince” could take away the prerogatives that belonged to St. Peter and his successors according to the words of Christ. When he was told that most of the English bishops had accepted the king’s order, More replied that the saints in heaven did not accept it.

On July 6, 1535, the 57-year-old More came before the executioner to be beheaded. “I die the king’s good servant,” he told the onlookers, “but God’s first.” His head was displayed on London Bridge, but later returned to his daughter Margaret who preserved it as a holy relic of her father.

St. Thomas More was beatified by Pope Leo XIII in 1886 and canonized in 1935 by Pope Piux XI. The Academy Award-winning film “A Man For All Seasons” portrayed the events that led to his martyrdom.

Salt of the Earth, Light of the World.

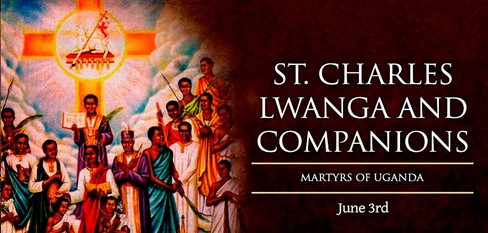

ST. CHARLES LWANGA – CATHOLIC YOUTH PATRON SAINT.

Charles Lwanga was a Ganda who belonged to the Bush-Buck (ngabi) clan. However, members of this clan were debarred by custom from the royal presence, and when Lwanga took service at court he passed as a member of the Colobus Monkey clan, that of his former master and patron. His father and mother are said to have been Musazi and Meme and it has been claimed that he was born in Ssingo County, and was a younger brother of his fellow martyr, Noe Mawaggali. Whatever the truth of this claim, it is certain that, at a very early age, he was sent to Buddu in the south west to be brought up by Kaddu whom some believed to be his biological father, but who may have been an uncle. Like Kaddu, his colouring was chestnut brown.

In about August 1878, Kaddu placed Lwanga, then aged about eighteen, in the service of Mawulugungu, the chief of Kirwanyi mentioned by the explorer H. M. Stanley. The following year the chief was transferred to Ssingo County, accompanied by Lwanga. On a visit to the capital in 1880, Lwanga became interested in the teaching of the Catholic missionaries and began to attend their instructions. When Mawugungu died in 1882, his retinue was dispersed and Lwanga joined a group of recently baptized Christians in Bulemezi County.

On the accession of King Mwanga in 1884, Lwanga went to the court and entered the royal service. His personality was such that he was at once placed in charge of the royal pages in the great audience hall, immediately winning the confidence and affection of his charges. Lwanga also excelled at wrestling which was the most popular sport at the palace. His immediate superior, the future martyr Joseph Mukasa, came to rely more and more completely on Lwanga for the instruction and guidance of the royal pages and for shielding them from the evil influences at court. Lwanga was also made overseer of the excavation of the so-called Kabaka’s (King’s) Lake, at the foot of Rubaga Hill.

On November 15, 1885, the day of Joseph Mukasa’s martyrdom, Lwanga and some other royal servants, whose lives were in danger because they were catechumens, went to the Catholic Mission and were baptized by Father Simeon Lourdel. The following day, the king assembled all the pages and demanded under pain of death that they confess their Christian allegiance. All of them, Catholic and Anglican, except for three, did so. Mwanga was baffled by the solidarity and constancy of the young Christians, but hesitated to carry out his threat to kill them all. Several times in early December the king attempted to intimidate his pages, in spite of visits from the Catholic and Anglican missionaries. On one occasion, Lwanga exclaimed that, so far from helping the white men to take over the kingdom, he was ready to lay down his life for the king.

After the fire in the royal palace on February 22, 1886, Mwanga moved the court temporarily to his hunting lodge at Munyonyo on the shore of Lake Victoria. Here Lwanga continued to protect the pages from the King’s homosexual advances and to prepare them for possible martyrdom. By this time, Mwanga had obtained the consent of his chiefs for a massacre of the Christians. Meanwhile, Lwanga himself baptized five of the most promising catechumens. On May 26, watched by Lourdel, the pages entered the royal courtyard to receive judgement. Once again, they were called upon to confess their faith. This they did, declaring that they were ready to die rather than to deny it. Mwanga ordered them all, sixteen Catholics and ten Anglicans, to be burnt alive at Namugongo. Once again, they passed the desolate Lourdel, waiting in vain for an audience. He noted how tightly they were bound, but more especially their calmness and even joyful disposition in the face of death.

The martyrs were taken from Munyonyo to Mengo and from thence on the eight mile journey to the execution place of Namugongo. On arrival, they were kept in confinement for a week. Preparations for the execution pyre were not completed until June 2. During that time the martyrs prayed and sang together, while the missionaries, both Catholic and Anglican, conferred among themselves and paid fruitless visits to the king to appeal for their young neophytes. On June 3rd, before killing the main body of prisoners, the executioners put Charles Lwanga to death on a small pyre on the hill above the execution place. He was wrapped in a reed mat, with a slave yoke on his neck, but he was allowed to arrange the pyre himself. To make him suffer the more, the fire was first lit under his feet and legs. These were burnt to charred bones before the flames were allowed to reach the rest of his body. Taunted by the executioner, Charles replied: “You are burning me, but it is as if you are pouring water over my body.” He then remained quietly praying. Just before the end, he cried out in a loud voice “Katonda,”–“My God.” After his death, the main holocaust then took place further down the hill.

Charles Lwanga was declared “Blessed” along with twenty-one other martyrs by Pope Benedict XV in 1920. All twenty-two were proclaimed canonized saints by Pope Paul VI in 1964. In 1969, Paul VI laid the foundation stone of the Catholic shrine at Namugongo on the place of Saint Charles Lwanga’s martyrdom. This shrine was dedicated on June 3, 1975, by a specially appointed papal legate, Cardinal Sergio Pignedoli.

Aylward Shorter M.Afr.

This article, submitted in 2003, was researched and written by Dr. Aylward Shorter M.Afr., Emeritus Principal of Tangaza College Nairobi, Catholic University of Eastern Africa.

© 2024. St. Joseph Catholic Laity Council of Nigeria, Agbor.